|

This is the tenth installment in a series about my trip to the West Bank in May 2015.

This morning our taxi was waiting at 8:30am as usual. Eleven women showed up. Some were in the Hijab, and others in tight levis, heavy makeup and no head covering. They came from a refugee camp outside of Hebron, from Nablus, and from Ramallah. A few had tried Yoga before, but most had not. I sighed as I once more dropped into the “beginners mind.” Please God, I prayed, give me patience with the simplest of teachings. Again I drew upon the memory of Swami Satchidananda. What would he say to my momentary impatience? I heard his voice reminding me that everything is sacred, the simplest of teachings, and that the Divine was in every person in that room. I took a deep breath and settled into the moment. Shraddha and I began with a little philosophy as to the physical, mental and emotional benefits of Yoga. Before they could start giggling with a distracted mind, as other groups had, we had them breathe and put them in poses so they could feel the affects of Yoga immediately. We all stood up to take the Mountain pose of Tadasana. We demonstrated how easily they could be thrown off balance by touching their back and moving them off their feet. Then we had them imagine growing down into the earth like the great roots of an olive tree and then out to the world like the branches of the tree. They also practiced standing as a mountain peak, growing upward while keeping the consciousness beneath the earth. It worked. When they tested one another to see if they could be easily toppled, they were unwavering and strong like the mountain. We explained that this was like moving out of the valleys where we cannot see and being able to rise to the peaks of the mountaintop where we have a more expanded view of life -- and the situations that arise all around us. After imagining growing into the valley beneath their feet like the olive tree that spreads it’s roots far and wide to grow it’s branches to the sun, they tried to push one another off balance but could not. They were firm, “like a rock,” one woman said. “This is the pose to use at the check points.” I reflected on our time at Qalendia, one of the worst checkpoints with the longest lines. “I practiced Tadasana,” I told the women. It is like a standing meditation that gives us greater patience, strength and a sense of inner empowerment.” They laughed but listened intently, I could tell, they too, were going to practice Tadasana when waiting at checkpoints. The next morning, they returned with renewed interest and positive observations. Shraddha and I noticed that there were emerging potential teachers in this group who expressed an interest in one day teaching Yoga to people in the refugee camps in Hebron, as well as to their friends and families throughout the West Bank. Their beautiful faces, which expressed eagerness and even hunger to learn more about Yoga, were unforgettable. After each workshop the faces of the students would appear to me at night as I held them in love and compassion with the light of healing and protection surrounding them. There is so much work to be done here. Even in the youngest person, the spines are bent with the weight of the occupation. They have the posture of one who holds the futility of broken dreams and future uncertainty. As we taught the three part breath (breathing into the belly, ribs and chest) and then the back breathing of the six part breath, their frozen backs began to move and the spine began to unfurl. Necks began to lengthen and some said their chronic neck tension was lessening and even disappearing. They felt more space inside, and a lightness in their body and their mind. We could see the changes the second day as the faces radiated a light that was not there the day before. This is the therapy of Yoga, I thought, the simplest and yet most deeply profound teachings. I could feel Swami Satchidananda nodding his head in approval as I remembered Mother Theresa saying, “It is far better to pick up a pin with the love of God, then move mountains without.”

1 Comment

The next morning, the workshop was to be taught the entire day by Suzanne, our colleague who works with Veterans with PTSD. Shraddha and I were worried the men may be stiff or tired and not want to return. As each of the men arrived one by one, we counted them hoping and praying that they would not disappoint Suzanne. When the 11th and final man came into the room, we sighed with relief. They all did come back and they all shared their experiences from the day before. One man for the first time had improvement in his back and his chronic sciatica. They all expressed feeling better, more energetic and yet more relaxed. Some said they went home and shared the Yoga and breathing they were learning with their families and friends. One man said he doubted Yoga would make any difference, because he had taken a Yoga classes before and hadn’t felt anything. He had assumed that this class would be the same. However, after the class, later that night and the next day, he felt many things and returned in the morning with renewed interest and belief in the benefits of Yoga. Their comments were all positive with some saying they would like to become Yoga teachers.

Shraddha and I took the afternoon off as the next day we were to teach a group of l0 or more women who are psychosocial counselors with the United Nations Relief Agency who are working with refugees. We were to give a workshop for them for two days with Suzanne and finally ... had a day off (maybe). Time to say goodnight to sleep a little before the 4am call to prayer. This is the eighth installment in a series about my trip to the West Bank in May 2015.

That night, we went to a film held at the Red Crescent building sponsored by the Swedish and British Consulate. The name of the film was “Speed Sisters.” Before the film was shown, there were the customary speeches by consulates of various countries as well as thank you’s and introductions of the film makers and four of the five Palestinian women who were the actual speed racing drivers who were the inspiration behind the film. The speeches were in English translated into Arabic as well as in Arabic translated into English. The film was also a combination of both languages. The audience was young with a vibrancy of creativity. Many ex-pat foreigners were among the audience and it was refreshing after being with women with traditional Muslim dress to make a leap into the future with young women in skin tight pants and high platform shoes and spiked heels. The “speed sisters” wore racy clothing and defied all the norms of their Islamic roots. The film was moving and inspiring not as to who won, but the obstacles they each had to overcome in themselves, as well as in their lives, to excel at what was traditionally known as a man’s sport. At the end of the film, the audience gave a standing ovation in honor of the speed sisters and the filmmakers who took five years in the filming. When the audience stood and applauded, I wanted to burst into tears because here it is, one more time, Palestinians giving hope to one another, to keep moving and lifting above one obstacle after another. When one of the women was criticized for speed racing saying she would give a bad name to her hometown of Jenin. She replied, “If I win, all of Jenin wins with me.” On the way home, I thought of nothing else but the film and how one of the woman actually flew the Palestinian flag on the back of her car in one race. As our taxi sped through the Saturday night traffic and narrow streets, I noticed all the Palestinian flags being flown and sold in shops along our way. Again, my mind drifted to the past, remembering the time of the Intifada when people were not allowed to have a flag. If they were seen with the Palestinian colors of the flag -- white, black, red and green -- they could be shot or arrested. Now the colors were brandished about as a uniting sign of freedom and self-determination. In the early 1990s, Palestinian youth, in defiant determination to declare their sense of freedom from the occupation, would dress in black and white and carry half a watermelon with the inside facing out, which was red and green. They then had all colors of their flag. It was a code of independency and bravery as they strode by the Israeli military presence who did not suspect, they were wearing and carrying the colors of their flag. This is the seventh installment in a series about my trip to the West Bank in May 2015.

At 3 am, I awoke to the call of prayer resounding through the hills of the outskirts of Ramallah. Then, after practicing Yoga for three hours, I lapsed into a very deep Shavasana for an hour before Shraddha and I dashed to the Yoga Center in downtown Ramallah. Our interpreter had not arrived yet but the men slowly gathered. They came through the checkpoints of Nablus, Hebron, Jenin, and others came from around Ramallah. They were tired, some from working three jobs and others working early morning and then standing in long lines to get across border checkpoints to travel from one town to another. We began by sitting cross-legged in a circle to hear their personal and service oriented needs as psychosocial counselors. They shared what their job entailed, and why they were drawn to Yoga. Two of the men who worked through UNRA, the United Nations Relief Agency, told of the work they were doing with the Bedouin tribes. First Khalid said, “They have much trauma because of continual exposure to Israeli forces and settlers. Our studies show that 44 percent of the Bedouin children are at a high risk of developing a psychiatric disorder.” Khalid continued saying that his job was so stressful because he took on the suffering of the Bedouin families. His friend and co-worker Mohammed continued, “The Bedouin’s culture and life-style is threatened by the occupation and continued building of the settlements. They are being forced off their lands along with their sheep, goats, camels and other animals.” Khalid chimed in again, “They cannot live in buildings like us, they would die. They have only known the nomadic way of following the water. Now, because of buildings covering the land, there is no water. They have to go great distances to find water.” As he spoke, I remembered the time before settlements when we would drive by the encampments of the Bedouin families. I always wanted to jump out of the car and join them in their nomadic life style in tents, with sumptuous foods and luxurious hand woven oriental carpets. Mohammed continued, “Their whole culture has been in existence for many centuries.” He shook his head with great empathy. “I feel the sadness from them in my mind and my body. I want to practice Yoga to help me lift above my sadness. I think then I can help them even more.” This amazing group of 10 men included physical education instructors, weight lifters and even a boxer. One man was a massage therapist and another distinguished older man was a retired high school English teacher. They were all serving the people in varying ways and wanted to practice Yoga to find more peace within and to relieve the stresses of everyday life. The greatest stress they all agreed upon was living under the unsafe atmosphere and unpredictability of the occupation. One father expressed his sorrow and anger when he was finally allowed to take his little children to Jerusalem. His voice broke as he asked, “How could I explain to them why the Israeli children have so much freedom, and a good life and can walk on the beach in Tel Aviv when my children cannot do the same?” The room fell silent as this sobering question hung unanswered in the room. Shraddha began again with the philosophy behind Yoga: Yoga Chitta Vritti Niroddha. That Sanskrit phrase means: Yoga is to still, quiet and calm the waves of the mind. All Yoga comes back to this simple statement that is the most difficult to achieve. We explained how emotions stem from the thought waves. We explained how the Yogic breath and postures are meant to quiet the waves of the mind. The men were interested, and then we began to have them breathe and eventually asked them to coordinate their breath with the movement of their back. In the Islamic culture it would not be appropriate for us, as women, to adjust the men in their poses. I demonstrated on our wonderful American Yogi, Rob. Rob could then adjust the men who needed it. Yes, it seemed like a brilliant idea, but not too far into the class, Alice came over and whispered in my ear that it was okay for me to adjust the men’s postures, because I was a grandmother. In their culture, grandmothers and great grandmothers were the only women, outside the home, who were allowed to have physical contact with the men. When a person begins to bend into Yoga positions it is possible to see their psychophysiological composition from the way they move or don’t move. Some of the men, even the gymnasts, were a bit muscle bound, and others had frozen fear built into the cells of the body -- especially in the shoulders, neck and back of the legs. Their spines were rounded as one who is beaten into futility. As we showed them how to straighten and strengthen the spine through a variety of simple Asanas, their competitive nature with one another began to surface. As one did something, the other would want to match his success. We tried in a variety of ways to slow down the waves of their mind by slowing down the rhythm of their breath and synchronizing this with the movement of Asana. Even though we were adapting and adjusting to the men’s capabilities in the poses they required us to simplify and then simplify again. The translations from English to Arabic were consecutive rather than simultaneous which required even more simplification. At one point in the class, Bashar, one of the men said, “Rama, if you want us to come back tomorrow, please … give us a break.” I said, ”No Break. Yoga is your break.” They laughed and groaned a little but continued on. Their bodies and mind needed these few simple practices to relax the habitually contracted muscles. To open their chests, which were protected by chronically rounded shoulders, we had them do back bends over chairs. It just so happened, there were only 11 chairs in the room and there were 11 men. I demonstrated and slid all the way to the floor into a handstand position and then brought my legs up. As I came out of the position, one of the young men half jokingly said, “That’s a torture position.” I wanted to cry, he was right. I remembered 23 years ago seeing the torture manual given to me by the broadcast journalists for the Boston Nova series. The reality of the Palestinian’s situation kept washing over me with alternating waves of sadness and joy. I felt joy to be here sharing Yoga but sorrow knowing just a little of what the people of the region have suffered. “Yoga is not to create more pain,” I said to the group. “It is a way to bring us out of pain -- mental, emotional and physical.” The men then eagerly grabbed their chairs and began to open themselves to the heavens as they looked back into the unknown part of themselves, the back body. As we led them into the Warrior Pose of Viravadrasana I, Bashar reached his hands to the sky and said he felt light coming through his fingertips into his arms and into his heart. His broken English and radiant face reflected the mood we call “bliss.” Bashar said, “I feel the presence of Allah. This is like prayer.” As we ended the class, the men seemed to let go into a deep relaxation. Later that evening, Shraddha and I wondered if they would come back the next day. This is the sixth installment in a series about my trip to the West Bank in May 2015.

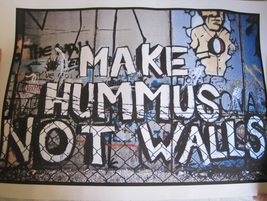

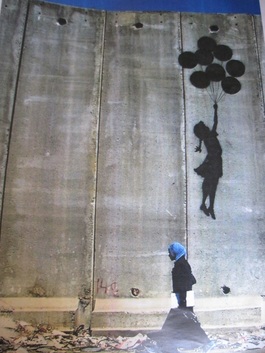

At dawn, we prepared for our adventure. Rob, his wife Alice, Sraddha and I now ventured forth by taxi to the border checkpoint of Qalendia between Ramallah and East Jerusalem. Rob was a veteran of these border crossings and knew where to lead us, in what looked more like confusion than danger. There were not the guns and officious looking soldiers as in the past. There was now a wall surrounding Bethlehem. I could not help but think of a Sunday sermon my husband Rev. Max once gave when he said, “The walls we build around us to defend, protect, and keep something out, are the same walls that keep something in. They can become the prison of our own souls.” We crossed over the “no-man’s gap” between one border and the next. Suddenly, we came upon multiple lines of Palestinians waiting to get through the narrow, metal-barred passageways that acted like funnels or chutes. I could not help but think of my home in Texas and the cattle, funneled through chutes into the trains or trucks that transport them to market and their own demise. So this is a checkpoint. Wow! Now I could understand what the yoga students had to go through to get to our classes from Bethlehem, Nablus and other areas and return to their homes each afternoon. No wonder they expressed fatigue and the need for greater strength and patience when standing in the checkpoint lines. As we joined in the lines with the Palestinians from many walks of life, I could not help but notice the changes from 20 years ago. My sorrow deepened as I witnessed a nation of broken peoples, broken dreams and no hope for self-determination and a country of their own. Older men once proud and defiant were clothed in tattered and worn suite coats that, like their families, had once seen better days. Their bodies, once robust with vibrant youth were now shrunken with the ravages of hopelessness. There are so many ways in all cultures of our world today to numb the pains of life. We were told there is now a growing reflection of this hopelessness through alcoholism and drug addiction. Today, I saw so many in these lines, whose light along with their life’s dreams had faded from their eyes. My own pain was so great, I wanted to burst into sobs but I too was now an automaton like in “Metropolis,” shuffling from one foot to the other as I slowly moved in the direction of the metal barred corridor to get to the other side of several turnstiles and Passport Control. Finally, we arrived at the taxis that could take those who could afford the fees to the border of Bethlehem. I was so grateful for this experience of knowing what some Palestinians have to live through each day just to go to work. Unemployment is severe and many did not have a choice when finding a job in another city. There were two foreign looking women in beige flack jackets that were helping to usher people through from the East Jerusalem checkpoints to the other side of Bethlehem. They were with the World Council of Churches. I asked one if they were still standing between the Palestinian people and the Israeli guns as they did 20 years ago during the Intifada. She was forthcoming with information that seemed to say that there had been changes for the better in some areas, but not in others. She shared stories that seemed to substantiate the continuing human rights abuse stories we were hearing from people in the region. The Church Ladies couldn’t stop the abuse, but they were there to serve the needs of the people and after a three-month mission, return home to decompress and share their stories with those willing to listen. We finally arrived at the home of our interpreter and friend. Her home was only 50 feet from the Bethlehem checkpoint, on the other side of the wall. She and her husband had a business of a restaurant and tourist shop also a few feet from the infamous border that now separates Bethlehem and the Arab sector of East Jerusalem. Our hostess’ home was magnificent with a marble courtyard entrance and marble floors throughout, giving a palatial feeling to what seemed like an oasis in the desert. They built the house to face the magnificent view of the Jerusalem hills just one year before the wall went up. Now, they had a view of the wall and beyond the wall of the controversial Israeli settlements that were taking over the hilltops of the West Bank. The home was spacious and well furnished with beautiful woods, and artwork. Our hostess, a yoga teacher in Bethlehem, had arranged for Shraddha and Alice to teach a children’s Yoga class in the Ida Refugee camp in Bethlehem. There were over 30 children, from ages six to ten. Like children everywhere, they were happy and restless, curious and reluctant. Along with our interpreter, they did a masterful job in creating movement, story telling, and then our Bethlehem hostess brought them into stillness and relaxation. Later as we met with the head of the school, he said that this camp held 6,000 refugees. The United Nations Relief Agency supported the camp and I noticed that Israeli militia no longer patrolled its streets day and night as in the past. There were no longer the curfew restrictions, and people seemed to go freely. Yes, these were permanent buildings, not tents. The principal of the school was born in the camp and his children were also born in the camp. The camps had become like neighborhoods, more humble neighborhoods that were attempting to create a better life for the future generations. After the class we attempted to go by the Rapprochement center but they were closed. Apparently this was a holiday. Our hostess took Rob and me back to her home since we had not slept for two nights and were exhausted. Sraddha and Alice were taken to teach a class of Muslim women in the Dheisheh refugee camp which was started in 1949. My memories of Dheisheh were pretty grim. I had an opportunity to change past impressions. The spirit was willing but the flesh was weak, so I opted out and fell into a deep sleep. Shraddha and Alice said upon their return that instead of ten women as was initially planned, over 30 women of all different ages from two to 50 years-old arrived. As the women kept flooding in to the room, Alice compared the scene to an American flashmob, where people receive a last minute call and rush to an appointed place. They said the smallest two-year-old Muslim yogini mimicked her mother in every pose. Sraddha said the women were hungry for yoga, even more than the yoga teachers we had just worked with. One woman’s sister had died from cancer one month ago and she asked Sraddha if yoga could help her overcome her unbearable grief. After the class she, along with five other women wanted to become yoga teachers to continue to work with the people in the camp. My eyes are filling with tears and my heart with gratitude as I write this. Twenty-five years ago, my husband and I walked the streets of Dheisheh refugee came when an Israeli soldier pointed his gun at my husband’s chest. My husband only gave back compassion and understanding, and the soldier relaxed his grip when he saw that we were not a threat. He then began to visit with my husband, sharing his personal story. At that time, the camp was under periodic 24-hour curfews. This meant that people could not leave their homes during these curfews to even get food or milk for their children. Dheisheh used to be one of the most futile camps where daily arrests, killings, tear gas use and human rights abuses thrived. For 25 years, I have held the Palestinian people in my heart and now, the demands for yoga here are so great, we are asked to return to Ramallah, Bethlehem, Nablus, Hebron and refugee camps of the West Bank. I wanted to cry with joy. A disempowered people under occupation can empower themselves internally through yoga. Regardless of circumstances around us, through yoga, we can always find peace and self-empowerment within ourselves. The day was ending, the sun was beginning to set. It was time to leave beloved Bethlehem and venture back through two checkpoints into the big city life of Ramallah. The once-thriving city of Bethlehem has been hard hit by the occupation and settlement building. The city was not as clean as it once was. Storefronts, block after block, were closed and shuttered permanently. The Church of Nativity that stands over the birthplace of Jesus was closed, we were told, because it became so badly littered. The city felt tired, listless and hopeless. Just a few tourist spots were open in comparison to what I remembered of the “Christmas City.” During that time, my husband and I were taking dialogue groups to Bethlehem and were teaching the Spiritual Essence of Conflict Resolution on the journey. The Christian community had glimmers of hope for their future. Now, I was told that a smaller percentage of the once thriving Christian community of Bethlehem and Beit Sahour, remained. As we left Bethlehem, the journey back over the border was uneventful but tiring. The next morning at 9 am we were scheduled to teach yoga to eleven men who were psycho-social counselors throughout the West Bank.  This is the fifth installment in a series about my trip to the West Bank in May 2015. Today was to be a day off, but one of our interpreters arranged for us to tour Bethlehem and while we are there, teach children and women at a refugee camp. The checkpoints from Ramallah to Bethlehem are difficult so it was suggested that we return to Jerusalem and then cross into Bethlehem from there, rather than go directly from Ramallah. This is one of the realities the people of this region must deal with every day. Even though life is difficult, they seem to rise above the challenges of the occupation, with humor, resiliency of spirit, faith, love of their families and of course, yoga! It is the fulfillment of my lifelong dream to see yoga spreading throughout the world. Wherever I have travelled or put on yoga conferences, the yoga community has a common language, and understanding that defies borders, stereotypes, prejudices, and separation. I have believed since the early l960s that Yoga is a way to bring peace to our world. It is not only a state of Union or “Oneness,” but it is the methodology to bring us to that state. The Islamic call to prayer began just before 4 am. I was usually awake to receive its inspiration. Every few hours until 9:30 pm, “the call” served as a continual reminder to pray and remember God as one arises, goes to sleep and goes about their daily lives. How wonderful I thought, even though Yoga is theistic as well as non-theistic, the call to prayer could be seen as “Iswara Pranidhana,” one of the most frequently mentioned practices in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. “The name of Iswara is Om,” Patanjali says in the first chapter. “Meditate and contemplate it’s meaning.” I thought, “How wonderful it would be if in Yoga, we had a continual reminder throughout the day to humble our ego and offer ourselves in prayer to the creator of us all.” What used to be a 15-minute journey from Ramallah to Jerusalem may now take one and a half to two hours. When my husband Max and I were taking groups back and forth from Jerusalem to Bethlehem and other parts of the West Bank, it was so simple. At that time, the time of the first Intifada uprising, the Israeli military had moveable makeshift barriers with barrels for checkpoints. They roamed the streets with their repeating rifles and set up guard towers and weapons stations on Palestinian rooftops. In 1990, my husband and I met one of these soldiers who shared his exceptional story that mesmerized us. His mission was to patrol the streets of Bethlehem. One day, he came across a Palestinian man who simply wanted to grow tomatoes in his front yard to feed his children. The occupation at the time was making it difficult to work or travel more than a few blocks. The Israeli soldier with a gun pointed at the Palestinian man’s chest threatened him with arrest or punishment if he did not rip out whatever he had planted. The man was non-combative and complied with the threat. When the soldier got off duty, he was on his way home to Jerusalem when a thought came to him. He had only viewed a Palestinian from the barrel of his gun. And perhaps the only Israelis they ever saw were in uniforms with guns. The soldier went home and changed out of his uniform and returned to Bethlehem that afternoon, to visit the Palestinian man’s home, wanting to get to know him, not as an enemy, but as a friend. Even though the Palestinian man was not allowed to plant seeds of tomatoes, the two men together planted seeds of trust. They began to dialogue, sharing their cultures, their experiences of the occupation, stories of their children and families. They explored cultural similarities and differences. It was such a rich experience for both that they continued to meet, bringing a growing number of friends to the meetings. The Palestinians were not free to travel so the Israeli soldier would bring his friends to Bethlehem to meet in the Palestine man’s home. They were hungry for this dialogue and when my husband and I were in Jerusalem, the Israeli soldier brought us with him to Bethlehem and included us, and our groups in their dialogues. Now, over the past 27 years this movement has grown into the Palestinian Center for Rapprochement Between Peoples. The brave founders of this organization catalyzed an ideal that now the youth are striving to continue. The work in dialogue and cultural exchanges is ever challenging in creative ways. It is especially difficult at this time since some universities and countries throughout the world are supporting and instituting Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS). Even though Israel sees BDS as anti-peace, the Palestinians and their growing supporters in other countries see it as a peaceful alternative for transforming human rights issues. Even though my original vision was to bring Israeli Yoga teachers to the West Bank, it is not at all possible at this time. I have always found geographical apartheid enhances stereotypes and fosters mental and emotional apartheid. Thinking of the BDF sanctions, I had a flashback of meeting with the Palestinian and Israeli founders of the Rapprochement Center when the Palestinians held one hand up high in the air and the other lower. “You cannot have dialogue when the parties are not on an equal footing. Israel is here,” he waved his upper hand, “and we are here,” he illustrated with his hand that was quite a bit lower. “To have real dialogue, we must become equal to Israel. His hands were now level to one another as he said, “You cannot have dialogue between the warden and the prisoner.” His Israeli counterpart, listened and nodded his head in agreement with his Palestinian friend. That night, a quote from the Mahabharata (The Great Epic of India) popped into my mind: “When one prefers one’s own children to the children of others….war is near.”  This is the fourth installment in a series about my trip to the West Bank in May, 2015. Sraddha and I awakened this morning with a groan. Barking dogs kept us awake until almost dawn. Our Ramallah hostess and organizer of our visit said that “since the bombing of Gaza, the dogs have been barking.” It was a hot night and now with only two or three hours sleep, we were facing a hot muggy day. Our taxi was waiting at the front door as usual to take us to the center of town for our final day of teaching. The women dragged into the room, fully garbed on this hot morning. Off came the Abaya, the black over-cloth covering the body and the Hijab that covered every strand of hair on the head. I took one look at them and changed the plans Shraddha and I had worked out the night before. “Let’s start with Savasana, the Corpse Pose.” A senior teacher, the only teacher in Nablus exclaimed with a sigh of relief, “Oh! I said coming through the long lines of checkpoints this morning that maybe Rama would give us Savasana!” Shraddha and I began with the alignment for maximum relaxation in the pose, and then went on to introduce how they could mentally and emotionally stay in Savasana as they practiced forward bends to lengthen the hamstrings and release emotional build up of tension in the calves. Their adjustments of one another were loving and tender. They seemed to have no fear of touching or being touched. Today we did not have a myriad of distractions as we had the day before when they had to be on the alert because a repairman was expected. Throughout these four days, their cell phones would have a rotating cacophonous ring tones, some in Arabic sounds and others in strongly audible melodious sounds. The women would not turn off their phones or apologize for its interruption, but would jump out of whatever posture they were in to take a call. It truly was like they were answering the call of God. Shraddha, Suzanne and I were astonished at first until we realized that in the continuing restrictions in this culture where one did not know what would happen from one day to the next, there could be any kind of danger or emergency. We did not ask them to turn off their phones as we would at home, but rose to a new height of understanding. How I loved these beautiful strong and resourceful human beings! Now, this last day, we put them in backbends over chairs and on the walls for shoulder stand, this time coming away from the wall. Shraddha led them in a long, much-needed Savasana (the corpse pose). Some of the women were already having less tension in their necks, and solar plexus. Their shoulders and spine were straighter and pains were disappearing. They loved the idea that all postures are Savasana, if they do the pose with an extended neck and a relaxed brain and mind, without effort and especially with the breath. One woman said that after only two hours, the swelling of her legs went down. Another young woman said the joint pain she had in the beginning of the week was gone and others remarked about feeling more peaceful, regardless of what was happening around them which included standing at the checkpoints. Shraddha and I had only about ten hours to work with them over four days, but their testimonies, radiant faces and loving goodbyes, said to us that even this small offering of ours was of great importance to them. I almost cried as the women were asking about the meanings of the Sanskrit sounds … and how, even in their strict Islamic culture … they loved chanting the sound of Om. Their voices and projection of the sound principle -- of the absolute -- grew stronger with each class. As I repeated Shanti three times, I explained, the first time it means peace with yourself; the second time, it means peace with your families, friends, co-workers and colleagues, especially peace to those with whom you have had challenges in the past; and third, peace beyond every border or boundary of nations, states and peoples, peace throughout the world. The matriarch of the group asked, “What did you say that Shanti means?” As I said, “it is the ancient Sanskrit word for peace,” she excitedly called out three times in Arabic to the women in the room, “Salaam, Salaam, Salaam.” (In Hebrew, Shanti, Shanti, Shanti would translate as Shalom, Shalom Shalom.) Tomorrow, we move to the Christian community of Bethlehem, from the Hebrew word Beit, which means house or dwelling place and - Salaam - of peace. Who knows what adventures and miracles will unfold in the path that lies before us! That night I couldn’t sleep at all. The winds were howling and I was so eager to get to Bethlehem that a child-like anticipation of the future kept me awake all night. Arabic words kept wafting through the portals of the mind as images of the Palestinian women kept appearing before me. The cells of my body were dancing every which way trying to reconcile the past with the present.  This is the third installment about my trip to the Middle East in May, 2015 We’ve been with the women in our classes for three days now. They are all Muslims except for one of our interpreters from Bethlehem who is Christian. The 13 Arab women would arrive each day fully covered in their Hijab, which includes two head coverings and an outer robe. Rob and Alice, who had supplied this Yoga center with blankets, blocks, straps and sticky mats came to the center each morning before we began teaching. The women would stay in their traditional coverings until Rob or any other man would leave. In their culture the only men who could see them without their headdress and robes were their husbands, brothers and sons. As one woman explained…even their cousins could not see them without their full dress. If a man entered the yoga room to deliver food or make repairs, they would either hide in a back room or put on their full dress. Under their Hijab, the women wore tight Yoga pants and long T-shirts. Some had glitters and one woman had a child’s T-shirt that had balloons as faces in bright colors of pink, lime green and yellow. I admired it and the next day she brought me a shirt just like it! I had forgotten. When you admire someone’s possession in that part of the world, it is an unspoken part of the culture to give it to you. I was raised in the Lebanese culture of my father and routinely gave away anything someone admired. Years ago, my English husband had to remind me that in America, this unspoken custom did not apply. When people admired things in our home such as oriental rugs, paintings and chairs, I did not need to give them away! The first of four days of class, the women were a bit reserved. They did not know us, or what were going to do. Most were Yoga teachers who taught in Nablus, Ramallah, and some in the refugee camps in Bethlehem. These teachers work with students who have every health issue imaginable. These areas are some of most acutely stressful in the world. The people never know when an attack from the military would happen, or when a bomb at the front door might explode in the middle of the night causing soldiers to storm the home, forcing men, women and children out into the streets. At times, several sources said that the boys as young as 13 or 14 would be taken to prison where some would be held for four or five years without trial, legal assistance, or communication with their families. One of the members of our group said her son was coming home after 15 years of imprisonment, without trial or being allowed to see or speak with any lawyer or family member. I sighed in futility and with hesitation, asked our translator about the torture methods once used by the military. She replied with sadness, “It is still going on but not as much, because the human-rights organizations have become more active and visible.” I held the sorrow in my heart that defied time. More than two decades ago, my minister husband and I witnessed human-rights transgressions by those who suffered so much before and during World War II. When we tried to speak of this to the Jewish community in the U.S. 20 years ago, thinking they would want to do something to stop it, they closed ranks to discredit the messengers, branding us as “anti-Semitic.” To even question the suffering inflicted on others was considered heretical. If a person was Jewish who questioned the actions of Israel, they were considered to be “self-hating Jews.” In the mid-1990s, I worked with the Israeli Yoga Teachers Association to hold a conference in Jerusalem, the theme of which was “Peace in the Middle East.” The Arabs were not allowed beyond the “checkpoints” and could not attend. However, it was a wonderful conference that brought forth contemporary masters of Yoga from around the world. The Israelis loved it. Indra Devi, Sri T.K.V. Desikacharya, Amrit Desai, Swami Dayananda and other leading Yogis from India and throughout the world were there. After the conference we took a smaller group into the West Bank to spread the message of Yoga to the Arabs who were not allowed to attend the conference. Now, two decades later, the young aspiring Yoga teachers in the West Bank are still not allowed to travel outside the region. Our visit was a time to create balance by focusing on teaching for Palestinians. I gazed with admiration at this group of beautiful women, social workers, psychosocial workers, teachers of children, hospital workers and clinicians, all intent on making lives better for themselves and others. They spoke the five little words that I have heard for 48 years of teaching, “Yoga has changed my life.” Through Yoga, they have found ways to feel free, even with the immense restrictions imposed upon them and their families in the midst of the occupation. Yoga transcends boundaries within us to give a sense of physical, mental, emotional and spiritual expansion in all areas of our life. What a perfect practice for this area of the world. I continued to say, “If we can’t have peace around us…Yoga helps us find the peace within us.” The women seemed grateful to be learning and being in an unfettered environment of communion with one another. In just three days, they have weaved their way into my heart where they will be held long after this trip is over. It was an unusually hot day and now the evening sky is angry with clashing thunder, lightening, the threat of rain and yet … no rain. Now it is time for sleep. |

Archives

August 2020

Categories |

Live Chat Support

×

Connecting

You:

::content::

::agent_name::

::content::

::content::

::content::

RSS Feed

RSS Feed